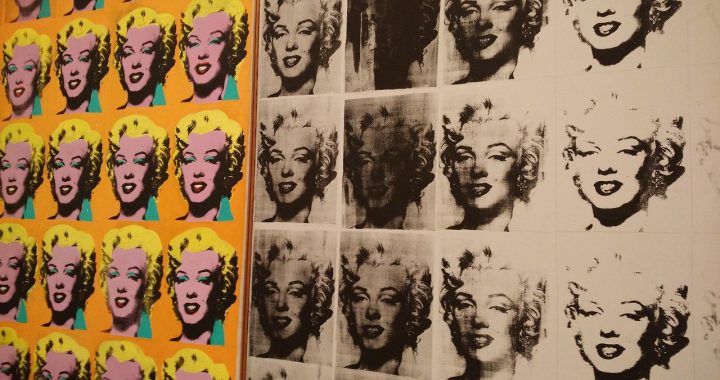

It was in 1964 that Susan Sontag wrote her notorious essay Notes on Camp, something which along with her provocative piece Against Interpretation rocketed her into the center of American society in a manner which effectively fused the worlds of high-brow literary culture with the sparks of streetwise ethos which at the time had begun to smolder in Andy Warhol’s legendary Silver Factory.

The description of camp provided by Sontag in Notes on Camp was essentially a list of the elements of a culture in reaction to typical bourgeois society, something in which Sontag herself was in rebellion at the time. Only the descriptions provided were deeply ironical in the sense that they were to be taken as satirical representations of various elements of American society rather than as things in and of themselves.

Camp was a means of embracing certain things while at the same time keeping a comfortably ironical distance from them. For instance, so-called “bad movies” such as Schoedsack’s King Kong, which the world of high culture viewed as being insignificant due to their lack of serious qualities, could now be seen as being not only enjoyable, but also having merit precisely because they were seen by most practitioners of high culture as being bad. In other words, what mattered was the irony of looking at something not only in terms of how good or how important it was, but in juxtaposition to a world that practitioners of camp sensibility saw as being overly serious.

Because there were unseen quotation marks around most aspects of camp culture, those which took the place of more serious literal discussions, camp irony soon became a powerful new form of communication among its practitioners. And because that type of intelligent humor is always an inside joke, understood only by those who get it, it soon came to exemplify for those who were in on the joke, a higher form of social intelligence.

Of course, this is also very much the function of irony in terms of intelligent communication with others, that the joke alluded to is always an inside one. That is, it is a means of putting others on who aren’t in on it. In so doing, pointing out how one’s position on certain ideas or issues is inherently understood by those who are in on the joke as being superior to other positions.

It is likewise a form of intelligence that is communicated primarily non-verbally through inflections in one’s voice, speech patterns that are tongue-in-cheek, or through such nonverbal dynamics as the twinkle in one’s eye; which means that the irony is never a means of communication with others that can be understood literally. Rather, it needs to be experienced, like camp humor in a manner that is both offhanded and offbeat; an indirect form of communication in which the way the message is delivered becomes just as important as the message itself; meant only for those who are aware enough to understand it.

When the knight in the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail who has both his arms sliced off announces to everyone that, “It’s only a flesh wound,” the aware viewer immediately understands that what he is doing is casting an ironical eye toward all those battle or crime movies in which the violence is both very real and very literal. That is, the filmmaker is putting on all those who favor violent movies with an indirect comment about them without ever alluding to them directly.

If irony is something that needs to be experienced primarily physically through voice inflections or facial mannerisms, the question of course becomes one of asking what effect our current digital age, when people are communicating with each other primarily by typing words out of necessity into a keyboard, has had on ironical expression. Obviously, when communication is that which removes physical expression from the equation, it becomes much more difficult to express oneself ironically.

One prime example of how entirely literal expression has out of necessity replaced ironical humor and intelligence is the current Internet acronym LOL, which as everyone knows stands for laughing out loud; an abbreviated reference which seemingly makes it veritably impossible to wink indirectly and ironically at one thing while actually referring to another simply because it is out of necessity so inherently literal.

Of course, the next obvious question to be considered, it would seem, is that of asking what effect this incapacity to express oneself ironically when confined to the parameters of a keyboard has had on our social and persona communication with each other? And furthermore, is irony itself a necessary ingredient for intelligent communication within wider social parameters? That is, what might be missing when we are deprived of it in significant ways?