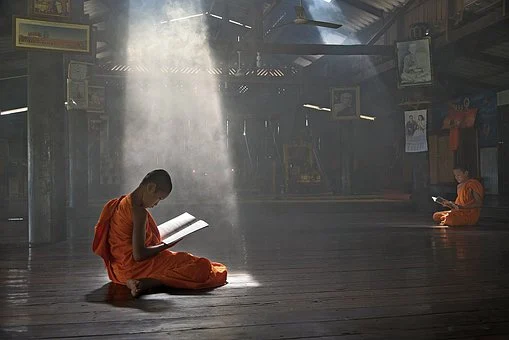

Lately there has been an increased emphasis on uniting the principles of psychotherapy with various meditation practices, such as those found in Buddhism, in order to promote what some have called the “wellness sector.” Of course, in the past psychotherapy and certain spiritual practice have been seen as existing at opposite ends of the spectrum in people’s search for peace of mind; psychotherapy being largely concerned with helping people face fully the very core of their anxieties by burrowing into them, while spirituality has traditionally been concerned with bypassing one’s unique neuroses in hopes of somehow transcending them.

However, lately those such as psychiatrist and practicing Buddhist Mark Epstein, in his recently released book The Zen of Therapy: Uncovering the Hidden Kindness in Life have sought to somehow synthesize the two philosophies by uncovering the fundamental principles that the two seemingly different approaches share. At one and the same time, emphasizing the uniqueness of our personal selves and life stories, yet likewise giving credence to the supposition of Buddhism that our personal stories are just stories that are in fact part of a larger reality in which they are much less substantial than we would ordinarily assume, Epstein attempts to create a larger, more inclusive approach to what therapy can do for people.

Yet, despite the efforts of Mark Epstein and others to unite psychotherapy and spiritual practices in the quest to improve people’s mental health and well-being, there might seem to be another possibility, one having to do with the potential shortcomings of each of these two endeavors. In fact, it may be possible that both approaches might be subject to making the same mistake from opposite sides of the spectrum. That is, psychotherapy intensely probing one’s emotional states in order to help the person in therapy better understand them, and spiritual practices such as Buddhism viewing certain emotional states as transitory, thus passing them by in order not to be trapped inside them.

In the case of psychotherapeutic practices, by intensely examining one’s emotions and feelings by essentially defining them with one’s thoughts, there is the possibility that by doing so the strength of those emotive states might be diluted because they are being examined at arm’s length, so to speak. In the case of spiritual practices such as Buddhism, by viewing those same feelings and emotions as being transitory, there is the possibility that one will not be able to experience them fully on the way toward a larger consciousness. In both cases, because one’s emotive states are being diluted, there is the distinct possibility that neither approach will lead the person undergoing therapy toward a larger awareness.

Perhaps wellness therapy, if one wants to use that particular term, rather than being seen as the practice of merely helping someone to better adapt to their world, and becoming content in doing so, might be seen as an exploration by therapist and patient alike, if one wants to continue using those terms, working to enlighten each other in the search for a greater awareness which might exist beyond the boundaries of the self. That is, exploring not only where the depth of one’s feelings and emotive states might eventually lead, but likewise examining how one’s thoughts and memories might in fact block such a realization from coming to full fruition.

With our current digital age having such a profound effect on our attention spans, the stream of our thoughts, and our working memories, we may need a new type of intelligence, one born in the depths of our sensorial and emotive lives, in order to more fully investigate not only the world we live in, but likewise what may lay beyond the boundaries of the self. Such an investigation would indeed be a journey worth pursuing in terms of changing the dynamics of the therapist-patient therapeutic model which has existed for so long. Perhaps using the power of direct insight people may be able reach the point where they no longer consistently need the benefits of either psychotherapy or spiritual practices such as Buddhism in order to understand the barriers to a greater awareness which our very own thought processes might be facilitating.

Lyn Lesch’s new book Toward a Holistic Intelligence: Life on the Other Side of the Digital Barrier was published recently by Rowman & Littlefield.